Looking for all Articles by Caroline Young?

International Women’s Day: The fight to read and write

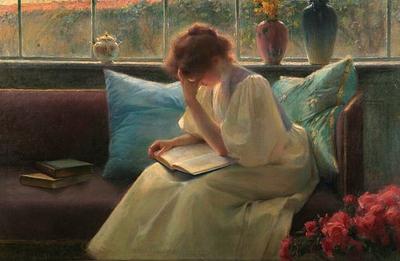

Throughout history, women’s right to write and even to read books was far from a given. From forgoing companionship to being locked up for reading, here’s a brief insight into how women in centuries gone by seized the right to read and write.

You might recall an image that did the rounds on social media a couple of years ago. It was an obscure list of reasons as to why women were admitted to insane asylums in the nineteenth century, and alongside ‘laziness’ and ‘political excitement’ was the eye-opening mention of ‘novel reading’.

Any sort of female independence at this time was typically equated with madness; those who stood up to their husbands, who read newspapers, and spent too much time with their noses in a book were seen as a menace. As the famous quote goes, ‘A well-read woman is a dangerous creature.’

In 1873, Harvard University medical school professor Edward H Clarke claimed that educated women struggled with infertility due to a conflict between the brain and the womb. He argued that women shouldn’t be admitted to the university because of the dangers that an overactive brain would divert blood away from her reproductive regions, leading to ‘hysteria’.

This kind of pseudo-science reinforced the societal belief that women should be content being wives and mothers, and that any ambitions outside of this were considered unnatural. After visiting a girls’ school in 1858 one doctor told teachers, ‘You seem to be training your girls for the lunatic asylum.’(this link will open in a new window)

Independent women in literature

The Gothic novels of the nineteenth century, including Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (with the ‘madwoman in the attic’) used the theme of female insanity to explore their oppression within a patriarchal society, and to question the laws that allowed for a woman to be easily declared insane.

Charles Dickens, who created one of the most famous, and unhinged, spinsters in literature with Miss Havisham, even tried to put his wife in an asylum because he wanted to marry a younger actress. Catherine Dickens was mother to his ten children, and a writer in her own right, and luckily the doctor he had summoned refused to diagnose her with a mental disorder.(this link will open in a new window)

Female authors at this time were similarly torn between societal expectations and the burning desire to express their inner lives through writing. They were aware of the battle they faced to be taken seriously, with many, like the Brontë sisters, opting to publish under the ambiguous Currer, Ellis & Acton Bell, and in the case of Mary Ann Evans, choosing George Eliot as a pseudonym.

To you I am neither man nor woman – I come before you as an author only. It is the sole standard by which you have a right to judge me - the sole ground on which I accept your judgement.

A hard-won right

Many women writers of the time were concerned that having a husband and children could seriously get in the way of their writing careers. Jane Austen’s novels may have been reflective of the Georgian woman’s occupation with securing a marriage, but the author herself opted out of finding her own perfect match. Her outlet in life was in writing, and she wasn’t going to sacrifice that creativity for the sake of a mediocre marriage. As she wrote to her niece, “Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without affection”.

Little Women author Louisa May Alcott knew from a young age that she didn’t want to marry, and instead chose to retain her independence as a teacher and writer. Spinsters were given a bad rep at the time for being severe and miserable, but Alcott proclaimed, “I put in my list all the busy, useful, independent spinsters I know, for liberty is a better husband than love to many of us”. She created Jo March as an alter ego – a strong-willed woman who turns down the marriage proposal of her best friend Laurie, because her desire to find success as a writer is unflinching.

There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.

Thank goodness that women over the next century fought for and won access to better education and were taken seriously as authors. We know that sharing stories with children can support development, and that writing and reading for pleasure improves wellbeing, increases empathy, raises self-esteem, improves employment opportunities and inspires creativity.

I have an inward treasure born with me, which can keep me alive if all extraneous delights should be withheld, or offered only at a price I cannot afford to give.

Let’s leave the last word to Jane Austen, who gave the Pride and Prejudice character Caroline Bingley these words: “I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of anything than of a book! When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library.”